Worship and Healing

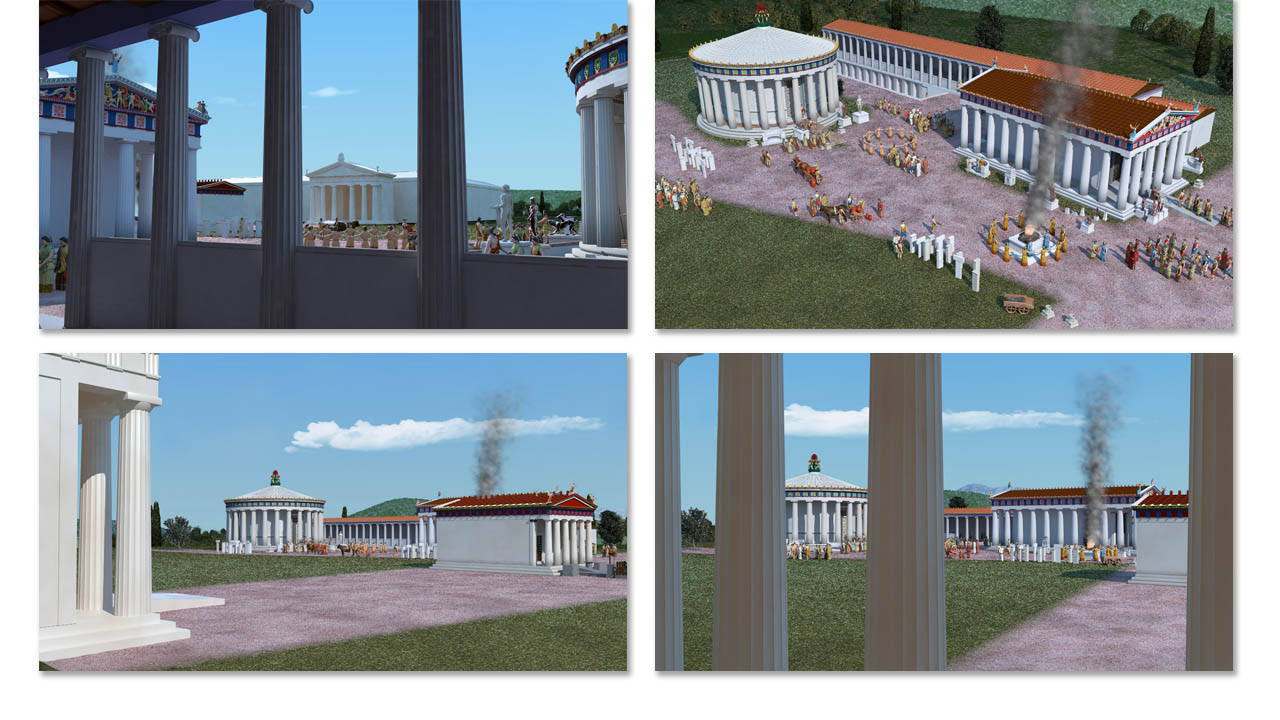

The healing sanctuary of Asclepius at Epidaurus was renowned as a centre for healthcare in antiquity. People flocked here seeking cures for maladies ranging from blindness, paralysis, epilepsy, and infertility to baldness, body lice, and insomnia.

Dreaming Cures

Worshippers would sleep in the sanctuary and, if they were fortunate, dream that the god came to them and performed a medical procedure (such as surgery, cauterisation, or applying poultices)

or prescribed a regimen to be carried out after they awoke.

The cured dedicated gifts to Asclepius; depending on the individual’s means, these might include marble plaques showing the worshipper in the company of the god or anatomical votives fashioned from metal, clay, wood, or marble that indicated the part of the body that had been healed.

Followers also came to the sanctuary to celebrate festivals in honour of Asclepius and his father Apollo. These festivals included contests in athletics and especially music. Plato writes about Socrates talking with a young aristocrat, Ion, who had just returned from a rhapsodic competition at Epidaurus.

Sound and music in the sanctuary

Music was integral to the daily worship of Asclepius and his father Apollo. Texts of hymns, some with musical notation, were inscribed on marble stelai erected in the centre of the sanctuary.

One inscribed hymn includes rubrics prescribing the time of day at which each hymn was to be performed, a text that classicist Jan Bremer describes as a “breviary on stone for daily worship.” There is no doubt that this sanctuary resounded with music, whether of small performances by and for intimate groups, or of large productions designed for a panhellenic festival audience.

Celebrating with song

The great theatre at Epidaurus, built by the architect Polykleitos and renowned for its acoustics, provided one venue for musical performance at the sanctuary. But there must have been other places to accommodate a variety of music and performances, especially among smaller groups.

The Thymele in the very centre of the sanctuary was an ideal locus for music, not only because of its acoustic properties but also because it was situated just next to the temple of Asclepius and opened towards a large altar. Those who had been healed might thank the god with music here; indeed, we know from another sanctuary of Asclepius, at Erythrae, that worshippers sang paeans around the god’s altar after they were cured.

Listen, learn and perform

Just as importantly, those in need of healing might have taken therapeutic benefit from listening to and even participating in performances within the Thymele. We know that the Greeks employed musical therapies. One tradition about the philosopher Pythagoras, for instance, describes how he would position those with physical and emotional ailments in a circle, place a lyre player in their centre, and have them sing and dance

to paeans to cure them. There are stories also of paeans healing those stricken by plague or madness.

Galen, who served as a physician to the Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius, remarks that Asclepius in particular was famous for prescribing the composition of music, as well as oratory and other forms of expression, as therapy.

Another devotee of Asclepius, Aelius Aristides, mentions musical performance and composition among the prescriptions he received from the god.

Healing Harmonics of Worship

We can imagine, then, that within the walls of the Thymele, the other-worldly resonances of the music may have worked a very real effect on the bodies and minds of worshippers. These individuals, transformed by song and dance, were healed while in the very act of praising the beneficence and power of Asclepius and his father Apollo.