Anasynthesis: the reconstruction of Pergamon in the Hellenistic and Roman Imperial times. In the Delphi project we saw Pergamene architecture beyond its homeland; we hereby evaluate it in its birthplace.

Particularly the Acropolis at Pergamon demonstrates the advanced technical know-how, the skills and efficiency of native architects and masons in adjusting the terrain to their needs (evident also in the monuments they dedicated at Delphi) and their ability to create an architectural regularity that would harmonize with the irregular topography. First and foremost among the aims of our project is a better understanding of the buildings’ form and the architects’ preferred solutions.

INSIGHT INTO THE HEART OF A HELLENISTIC KINGDOM AND ITS ARCHITECTURAL LEGACY

Professor Elena C. Partida

On an abruptly sloped mountain, naturally fortified and overlooking a fertile plain, once upon a time rose the Acropolis of a kingdom, whose artistic and intellectual qualities rivalled its martial virtue and fuelled its prosperity; a kingdom determined and qualified for putting an end to the Gauls’ incursions, but also aspiring to model its architectural tradition on the building programs of Classical Athens. The king dreamt of recreating the glory of Athens on the heights of Pergamon.

The range of archaeological finds at Pergamon offers a glimpse into the Hellenistic kingdoms, as they had been formed in the early 2nd century BC. Within the Acropolis enclosure, the consecutive artificial terraces and the arrangement in individual sectors indicate the allocation of space to specific pursuits, religious, civic and administrative, as suggested by the storerooms and cisterns providing for, in case of besiege. Such an organized spatial layout facilitated modifications and remodelling in the long-term. Near the palace, the temple of Athena Nikephoros (victory bearer) emerged surrounded by a complex of stoas and the Library, not far from the great altar of Zeus, likewise established on its own, autonomous artificial plateau. Civic activities were held in the upper Agora, while the theatre stands out with its excessively steep koilon (seating area), built practically on the verge of a cliff and bespeaking the ancient builders’ mastery.

Possessing the technical know-how and expertise, they managed to turn the sharp natural inclination to their advantage and, therefore, to lay out unparalleled vistas from various altitudes and perspectives. The strip-like oblong terrace offered an ideal promenade slightly below the summit, culminating in the temple of Dionysos, patron of the art of theatre and entertainment. His temple was severely damaged by fire but rebuilt and refurbished by the Romans, who favoured spectacles in general. The oblong terrace was fringed by a massively buttressed stoa, tentatively interpreted as sheltering athletic training and competitions. The apogee of the Pergamene School of architecture highlights the adaptability of the stoa, a building type that the architects of Pergamon advanced and the kings of Pergamon commissioned as votive offerings in panhellenic sanctuaries of the Greek mainland.

Every facet of a Hellenistic city is represented in Pergamon: the religious and cultic, the public and civic, the heroic, the royal, the intellectual. Perhaps for this reason the site remains highly attractive, not only for archaeologists. The city’s well-arranged configuration was due to systematically planned building programs, comparable to those carried out in classical Greece, despite the different political regime. Here the king was the patron of the city and protector of its people, supporter of culture and education, of science, arts and athletics. In the heart of the city of Pergamon, the layout of the Acropolis reflects the sovereign’s institutional authority, the concentration of all powers in his hands. This was sanctified, and visually ratified, by the proximity of the palace to the sanctuary of Athena.

The ‘plateia’ or courtyard fringed by porticoes was a spatial feature of the Hellenistic age, applied in agoras and sanctuaries alike. Usually a nearly rectangular space was framed by stoas along two or more of its sides. The position of the temple of Athena Nikephoros on a ‘plateia’ (piazza) bordered by L-shaped, two-storey stoas may seem floating in terms of axial alignment; this, however, indicates that the temple already existed while a building project in its immediate surroundings aimed to expand and monumentalize the sanctuary. Inside the stoas, niches (recesses) cut into the rear walls probably received statuettes. In the years to come (Roman Republic) the decorative motif of niches can be found on the outer face of walls. Noteworthy, however, about the stoas of the Athenaion at Pergamon is their aesthetically harmonious hierarchy of architectural orders, with an outer Doric and inner Ionic colonnade at ground-level, whereas the upper storey displayed engaged Ionic half-pillars on the outside and Aeolic columns with volute capitals along the interior long axis.

Conforming to the typical characteristics of Hellenistic architecture, and therefore two-storied, was also the propylon (gate) into the sanctuary of Athena Nikephoros, an intriguing structure in terms of its potential function. The upper storey of this porch had closure-slabs between the Ionic columns and was generally ornate in style, topped by a pedimental roof. Taking into account the overall layout of the Acropolis, one notices the topographical proximity of the Athenaion to the palace, which lacks an open-air space. In this respect, the ‘plateia’ of the Athenaion could have served as the official royal court, where the king would address his people. It is then possible that the upper storey of the propylon/porch was used also for the sovereign’s public appearance before the gathered crowds.

By the imposing scale, elaborate design and grandeur of the altar of Zeus, the architects of Hellenistic Pergamon pushed the limits of sacrificial structures. The altar is elevated on a lofty substructure decorated with the dramatic sculptural narrative of a cosmogony.

The altar’s frieze forged the physiognomy of the Pergamene School of sculpture, which was to influence generations of artists to come. Divinities, heroes, imaginary and daemonic creatures step out of mythology, to be carved in marble nearly in-the-round and to be expressively portrayed in vivid motion, passionate gestures, violent encounters and agitation. The frieze illustrates the battle of the Olympian Gods against the Giants, recalling the subject-matter of the (Archaic) Siphnian treasury at Delphi, fashioned in an entirely different style.

The frieze, in fact, decorated the lower part of the altar. However, it is the superstructure that turns this monument into a major architectural accomplishment. Colonnades outline the altar’s perimeter, as well as the wings flanking the grandiose stairway. The purpose of these colonnades is strictly ornamental, since they are situated too close to the walls to allow a functional ambulatory. The ritual core of the altar formed a shrine on its own merit, where yet another component of Hellenistic design was accentuated: the open-air court.

Discordia concors or “harmonious discrepancy” is considered to characterize the art of the Hellenistic age. Hellenistic architecture is pervaded by a tendency for experimentation in bringing together disparate and seemingly inconsistent or even contradictory architectural elements into a coherent entity. How this would be integrated into the landscape, was effectively planned in advance. Natural environment and topography would eventually bind and unify all the architectural components. The architects of Pergamon knew that the landscape provided a steady, calm backdrop for observation and for their artificial creations to be set against.

The current 3D model

The preliminary 3D model shown here is based on the drawings, ad hoc studies and research conducted since the 19th century by R. Bohn, L-M. Collignon, Th. Wiegand, D. Strong, W. Radt, W. Hoepfner, H. Lauter, J.J. Pollitt, J. Rohmann, V. Kaestner, A. Scholl, D. Gilman Romano.

Affording an overview of the Acropolis from various angles/standpoints, the model poses questions regarding, for example, what portion of the original design was preserved in a refurbished monument, what further spatial adjustment this necessitated, the winding access to elevated buildings, the form of windows and their precise position depending on function, etc. Some answers may be provided partly by the monument’s setting, the neighbouring structures, the topography; this is the value of assessing superstructures in relation to each other.

Even in an individual edifice, the effects of a conversion or enlargement upon roofing and illuminating, for instance, become obvious when the volume of the respective building and its premises are rendered three-dimensionally. The current model tests details of design, vista and axial disposition against the available archaeological evidence. Above all, the model is a tool for evaluating architecture proportionately, relatively and comparatively.

In 2021 we return to question some generally accepted, yet contentious, proposals and to reconstruct as accurately as possible, based on up-to-date scientific studies.

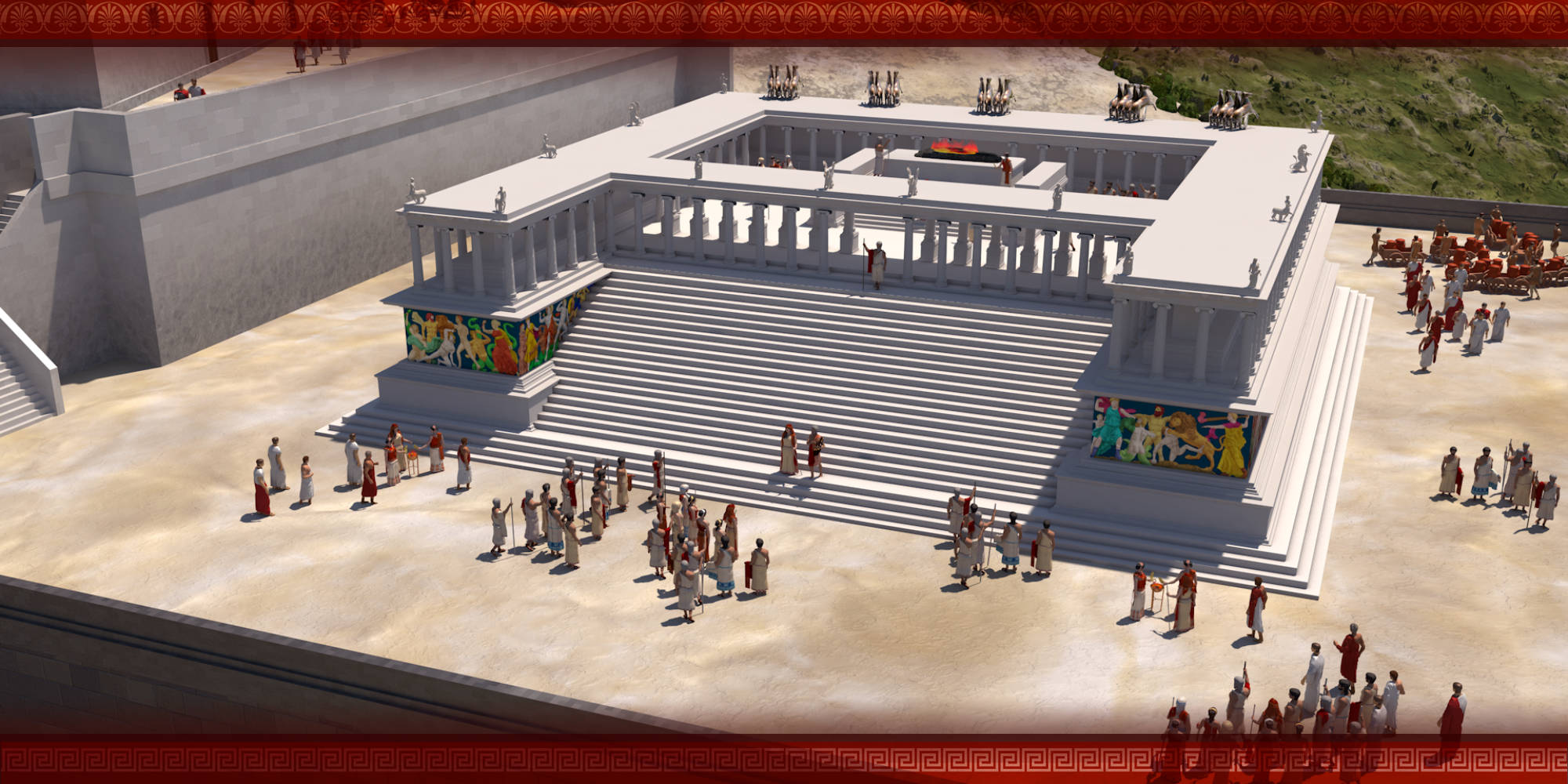

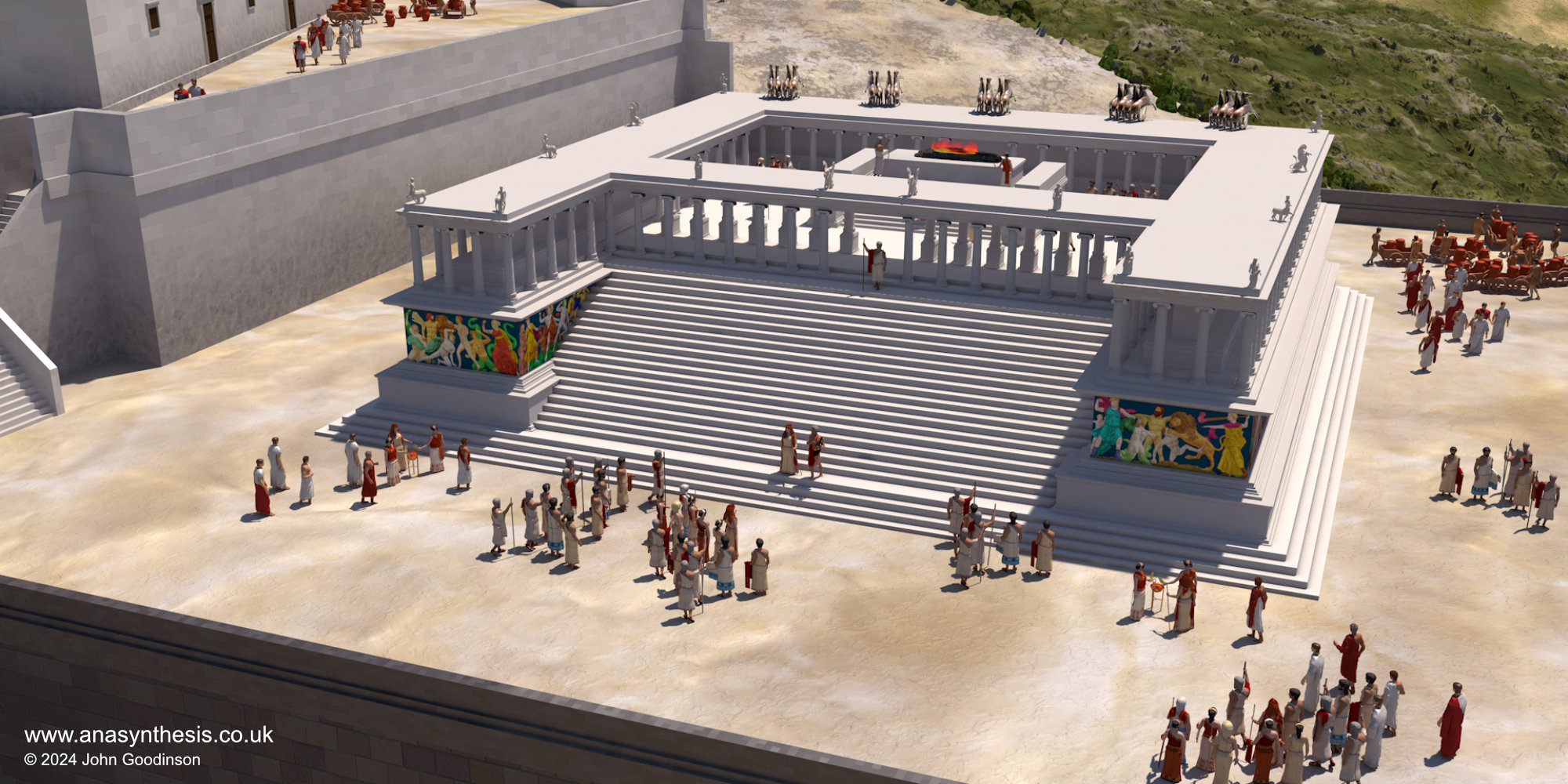

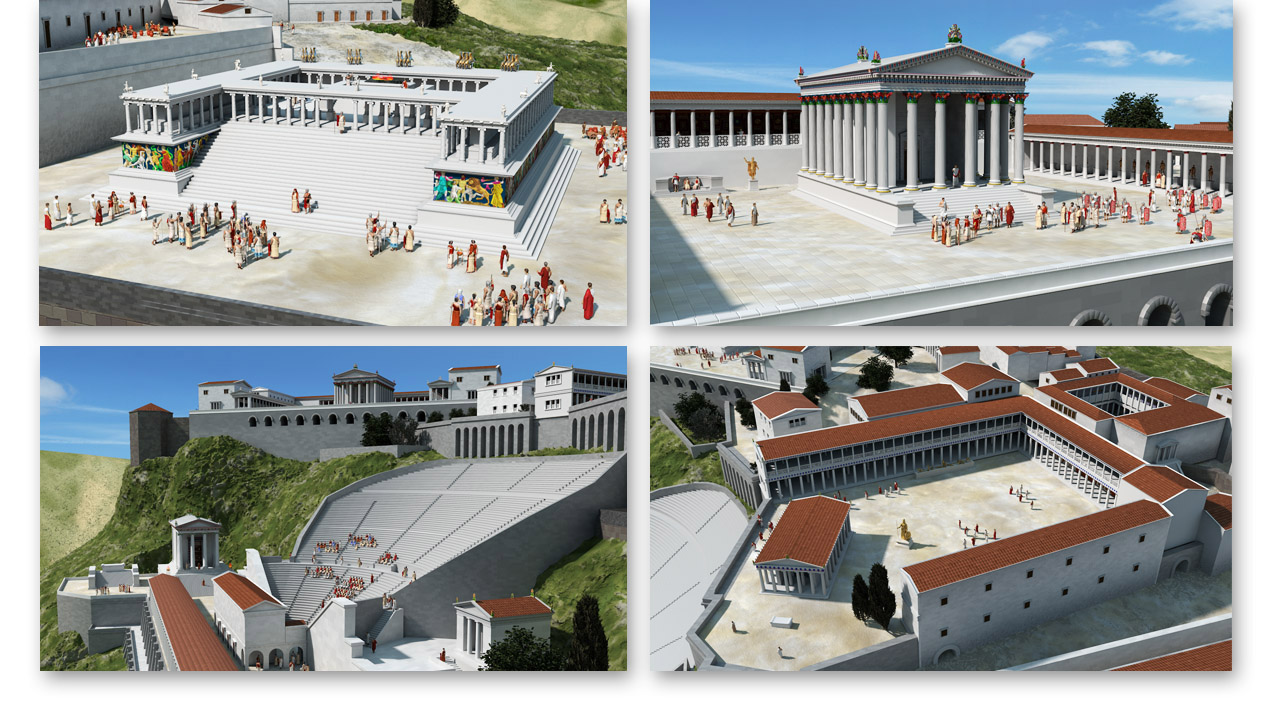

Reconstructions above:

The Great Altar, which dominates the Acropolis of Pergamon, was dedicated to the cult of Zeus or to the Twelve Gods and the deified King Eumenes II jointly, as put forward by Fr. Queyrel on textual evidence. The structure is very complex to grasp, in terms of architectural synthesis. Our preliminary reconstruction provides the "currently accepted" layout.

The temple of Trajan, of the Roman Imperial period, was built in the Corinthian order and dedicated to Zeus and Emperor Trajan. Like the temple of Athena, it was surrounded by stoas, yet built of dazzling white marble, rather than the local trachyte/limestone. On its prominent locality, the temple of Trajan afforded impressive vistas over the theatre terrace. The terrace of the Trajaneum was contained by a massive retaining-wall with vaulted substructure. The development and dissemination of the vault, an innovation in structural technology employed also in the Pergamene dedication at Delphi, has been accredited to the architects of Hellenistic Pergamon.

The imposing theatre at Pergamon and, next to it, distinct in its solitary location, the temple of Dionysos. Shown here is the temple as re-erected by the Romans on a podium (raised platform) veneered in marble and bearing an elevation in the Ionic order, as opposed to its Doric predecessor. The other half of the terrace is occupied by the altar of Dionysos, adjacent to the temple, instead of axially aligned to the latter’s entrance. Although monumental and refined per se, the altar of Dionysos is dwarfed by the gigantic one erected in the Hellenistic era for the cult of Zeus.

The temple of Athena was built probably in the late 4th century BC but the sanctuary was considerably enriched, reshaped and renovated after the Pergamene troops had defeated the Gauls in the 3rd century BC. Victory was empowered by goddess Athena Nikephoros and commemorated by the respective building program.

The Propylon (below) defined a monumental entrance to the sanctuary of Athena Polias, patron-goddess of the city. The carved balustrade on its upper storey features booties and trophies despoiled from the defeated Gauls - a relief representation that echoes the epithet of goddess Athena as Nikephoros, i.e. victory bearer.

Anasynthesis would like to thank professor Elena C. Partida once again for her extensive scientific guidance for the reconstruction of our preliminary model of Pergamon. This article has been especially written for the announcment of our Pergamon project commencing in 2021.

Link: academia.edu